2/ Prequel

In late August, 1979, Renee Durbach, a Cape Town journalist was interviewing me about the decision to close The Space. ‘Why now?’ she asked. There were many answers to this. Finance and the difficulty of attracting audiences to Cape Town’s (then) deserted centre were just two. However, the answer I gave was different. ‘When the idea was born, back in July 1971, I didn’t know The Space was impossible. Now, eight years later, I know every reason why it is – and that cripples me.’

Thinking back now – more than 30 years later – it still seems to have been a time filled with the dauntless innocence of indomitable youth. In 1971 a group of hopeless optimists gathered together in a small city at the bottom tip of Africa, 6000 miles from anywhere, and did the impossible because they didn’t know any better.

How did this happen?

To answer that question we have to go back even further. Imagine yourself at a generic Cape Town party, sometime in the late 60s. ‘Generic’ because the process took shape over quite a few of these raucous, frequently drunken, do’s.

In one corner sits a young observer. He is observing mainly because, at this stage of his life, he was very shy of, and over-awed by, the people at the party. Born in the small country town of Paarl, this gauche, unsophisticated hick – let’s call him Brian – is new to the racy ways of The Big City. He is married to one of South Africa’s top actors, Yvonne Bryceland – which is how he has managed to gain entry to tonight’s party. His observer status also comes about because he has built a career as a photojournalist who specializes in theatre, ballet and opera. In that wonderful, fertile area in Cape Town these parties were attended by a rainbow of colours, genders, crafts. Actors mixed with poets, dancers hung on the words of writers, painters argued with sculptors, homosexuals chatted with heterosexuals (this was back when gay meant absurdly happy). The entire range of South Africa’s multi-cultures was there – Black, White, Brown, European, Non-European, Coloured, Indian, Malay – all of the bewildering array of tags inflicted by a government that had gifted the World with the reality of Apartheid. They spoke Afrikaans and English, and sometimes a mixture of the two. There was one common thread that brought these artists together – they all opposed this system

Part of the reason for this was one man. Athol Fugard.

Already accepted by this group as South Africa’s greatest playwright (in a very small field), he had gained international fame with his play, The Blood Knot. After this was produced in New York the Nationalist Government took his passport from him, subjecting him to the delicacies of surveillance by the Security Branch. As these things often do, this action had also conveyed upon him the status of Hero and Martyr. Even among the many luminaries present he was regarded with admiration and respect. Most were his close friends. Present would have been a goodly section of the Afrikaans group known as Die Sestigers (The 60s), among them writer, Jan Rabie, poet, Ingrid Jonker; other writer/poets like James Matthews, Richard Rive; painters, Marjorie Wallace, Eric Laubscher, Claude Bouscherain; theatre directors, Mavis Taylor, Robert Mohr; actors Bill Curry, Wilson Dunster, Val Donald, David Haynes; jazz musician, Midge Pike; dancer, Gary Burne – among many, many others.

They were a loud bunch. Any party fuelled by the rotgut of Tassies (a red wine, Tassenberg, scraped together from the leftovers of multiple other barrels of already cheap wine, bottled in large, half-gallon glass jugs, and sold at rock bottom prices) would have to be. It was at one of these generic parties that I first observed Bill Curry, later to become one of the central actors at The Space, in loud and vehement argument with Richard Rive. Both would have been categorised by the Government as Cape Coloured. By then my small-town background, which had fed me with prejudices that led me to grow up believing that the other races were still developing towards a level of Civilisation where they could aspire to be more than just teachers of their ‘own kind’, had been well and truly smashed by contact with ‘kinds’ who were very obviously intellectually superior to me. It was a steep learning curve.

My own first connection with Athol had come in 1961. On a boiling hot summer’s evening I had gone to collect my new ‘girlfriend’, Yvonne, for our first real ‘date’. I had met her when I took a summer vacation job in the Cape Times newspaper library. At first overawed by her ‘fame’ as an actor on radio, plus the fact that she was 16 years older than I was, a divorcee with three daughters, any possibility of anything more than just being good friends seemed out of the question. But things had changed. So here I was chugging along in a clapped-out old Humber, borrowed from my friend, Roy Webb. I was still in residence at College House at the University of Cape Town, vainly pursuing my stab at becoming a librarian. This ended when I discovered that librarians were not supposed to read the books. My friends, Art Clarke and Andre Uys, had orchestrated this first clumsy attempt at a date in despair at my callow inexperience. I had shyly asked whether she would like to see the new play that was causing such a stir. To my amazement and consternation, she had consented. Prior to this my only experience of taking someone out had been an ill-fated and excruciating evening in the Protea Bioscope in Paarl, my best friend, Carl, and I sitting in frozen silence between the Hugo sisters, both of whom I was wildly infatuated with, while Carl’s experienced and worldly-wise cousin, J.B., schmoozed his way around the aim of the evening, his attempted conquest of Marina. He had coerced us to be his rather pathetic ‘wingmen’. It was one of the worst evenings of my life. The fact that I had lived in the same street with all three of the girls involved since I was five years old should give you an indication of the staggering level of my shyness and unsophistication.

But enough of that. This was different, even though it was not an evening without incident.

In the first place, Roy’s Humber had a heating system that was stuck on ‘On’. And only one window would open. By the time we had made the journey from her extraordinary, broken-down, rat and cockroach-infested flat in Surf Edge, Bantry Bay – repository of many of my sweetest memories – we could probably have been served with Sauce Bernaise.

The Blood Knot was being staged in the hall of the Orange Street Synagogue. As it had a mixed cast – Athol and Zakes Mokae – the play could not be performed in a ‘proper’ theatre.

The auditorium was packed. The heat was intense. There was an undercurrent of excitement. The play was late in going up. Minutes ticked by. Finally the Cape Town producer, David Bloomberg, stepped thorough the curtains and apologetically announced that there had been a problem with the lighting board, and that the play would be presented with only one lighting state, and not so much as a fade-up or down. The melting audience accepted this with sweaty stoicism. The curtains opened on a scene with a table and two chairs.

Three hours later Yvonne and I staggered out into the Cape Town night. More than one thing had changed in our lives.

Neither of us could believe that three hours had passed. It felt more like 30 minutes. Yvonne had known Athol previously when he and his wife Sheila had staged esoteric plays together in the late 50s, during his stint with the South African Broadcasting Company. Not very well, she said, she had been rather intimidated by their intellectuality. Unquestionably, however, for both of us, we had heard a voice that spoke to us in our own language. It didn’t matter that the two characters inhabited a world ‘on the other side of the tracks’ from us – they were unmistakably, indelibly South African.

Three years later we were married. Yvonne took the plunge into professional theatre, which had opened up for the first time with the creation of the Cape Performing Arts Board (CAPAB) – the South African regional equivalent of the National Theatre. At the age of 39 she was finally able to practise her craft. After three years as a journalist with the Cape Argus, I became a professional photographer, and, in 1967, the next connection came.

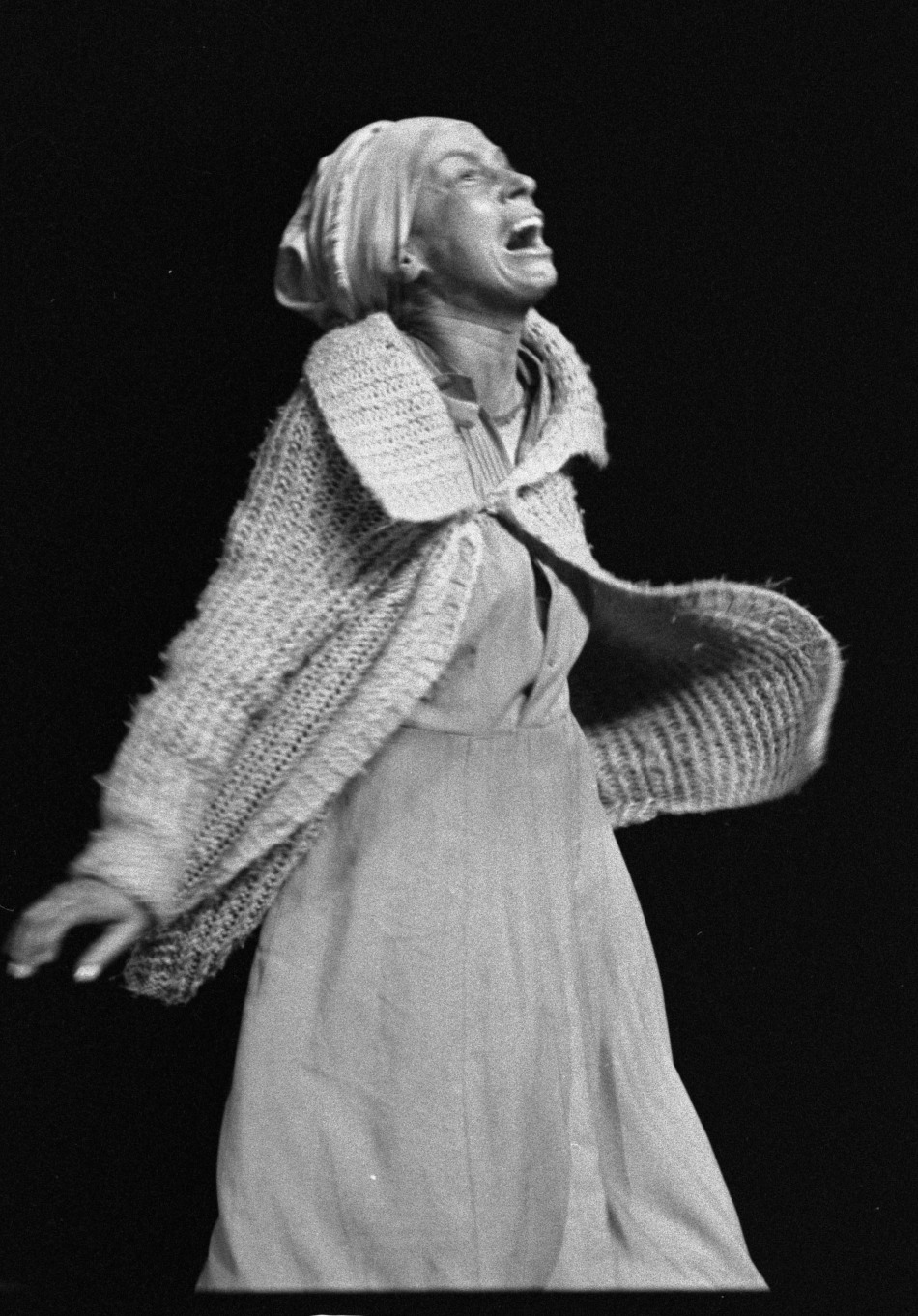

Athol returned to Cape Town with his new play, Hello and Goodbye. This time – the play featuring two White characters – it was able to play in a ‘proper’ theatre. The Labia is about 200 yards from the Synagogue hall where we first saw The Blood Knot. This time everything worked. The theatre was air-conditioned. Athol and Molly Seftel inhabited the ‘Poor White’ Port Elizabethan world of Hester and Johnny. Once again theatrical magic was created.

Yvonne was supplementing her acting income by writing an entertainment column for the Cape Times. She went to interview Athol. A thought was born. A year later Athol and director, Barney Simon, arrived at our flat in Kriskit, looking down over Clifton beach. They were wanting to stage Athol’s People are living there. In Johannesburg. They wanted Yvonne to play Millie, the menopausal landlady who towers over her dysfunctional tenants. This would mean that Yvonne would have to resign from CAPAB. It was a big step. I had just turned professional, it was freelance work, and not at all secure. But there was no alternative. Yvonne was getting stifled by the diet of stale imported plays that CAPAB was staging. She went to hand in her resignation. They asked to see the play. Then offered to stage the premiere. Proper funding and security!

Athol arrived back in Cape Town at the beginning of 1968. He was to both direct the play and act the role of Don. CAPAB allocated a three-week run, unsure of the pulling power of a new South African play. It opened on a Saturday night. On the Monday, before the crits had time to register, the entire run was sold out. The excitement was immense. London producer, Peter Bridge, came to see it and started making plans to transport it to the West End, told Yvonne she should change her name – Bryceland being too long for the lights outside a theatre. She refused. The transfer never happened. Much later I heard that a group of London producers had planned to club together and stage small-scale, risk-taking plays in a London venue. Bridges thought that People would be perfect. When he got back to London the project had fizzled out.

The play was taken on by Mannie Manim of the Performing Arts Council of Transvaal (PACT) for a run at the Alexander Theatre in Johannesburg, where it was equally successful.

Athol was working on his next play, Boesman and Lena, which had been commissioned by Prof Guy Butler of Rhodes University. CAPAB offered to share the deal, excited by the success. The play premiered in Grahamstown in July 1969, then moved to the Hofmeyr Theatre, CAPAB’s Cape Town base, in November. Despite Athol’s trepidations it was given a four-week run, extended to five when the audiences flocked. It toured to Johannesburg and Durban through 1970.

CAPAB were delirious. They offered Athol their entire company if he wished, with which to create a new piece. He chose Yvonne, Val Donald and Wilson Dunster, and retreated into a rehearsal room over the Labia Theatre. 10 weeks later they emerged, to CAPAB’s great consternation with Orestes. It was an end and a beginning.

It was over this period, from Athol’s arrival in Cape Town, that the party season really began.

Pardon me for skipping lightly forward. Context was needed.

What increasingly happened at these parties was a moment among the actors, directors and writers when somebody would groan: ‘If only we had a space in which we could do our own thing…’ (It was the 60s, remember?) This became a haunting refrain, and it fed into the changes that were happening to me – the changes brought about by Orestes. Somewhere along the line the seeds that Orestes had sown, germinated, subconsciously. Somewhere inside me I became impatient with the ennui of the constant refrain. Somewhere deep inside a new thought, a new possibility started to grow.

In London, in 1971, it forced its way out of the thick soil of my psyche, and began to unfurl its petals.

Enough of this laboured metaphor.

I sat in the basement that was The Open Space and thought: ‘This couldn’t have cost much.’ Famous first words…